An Interview with AC Think Tank Author Seán Fobbe, Part II

In the second of a three-part series, we sat down with Seán Fobbe, Chief Legal Officer of RASHID International and author of the AC’s How to protect outstanding cultural heritage from the ravages of war? Utilize the System of Enhanced Protection under the 1999 Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention. Fobbe discusses the unique challenge of cultural heritage preservation in Iraq; the difficulty of prosecuting war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide; and broader patterns in cultural crimes worldwide. Read Part I of the interview here.

What are some of the difficulties you face in prosecuting the destruction of cultural heritage in Iraq?

Certainly one of the major difficulties in the Iraqi context is the lack of territorial jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC), as Iraq is not a State Party to the Rome Statute, with neither ad-hoc jurisdiction nor a Security Council referral forthcoming. The domestic criminal agencies and courts in Iraq are currently not equipped to handle complex war crime investigations and trials, with judicial responses being mostly quick, lethal, and lacking in due process. We therefore place great hopes in the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD), established following UN Security Council Resolution 2379, who are currently gathering evidence for international and national trials against Islamic State fighters.

In such challenging conditions, what viable options do you see for prosecuting war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in international fora?

One is the principle of active personality under the Rome Statute, by which perpetrators who are nationals of a State Party to the Rome Statute can be prosecuted before the ICC, even if the State where the crime was committed is not. Due to the large number of foreign fighters flocking to the banners of the Islamic State in the past, I expect this option will be quite relevant to the ICC, though it is hard to say if the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) will pursue it.

Another option is the principle of universal jurisdiction, under which every State in the world may prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Despite this, it is challenging to convince an entirely uninvolved State to expend the substantial resources required for such trials and even advanced economies may find it difficult to procure the necessary evidence from abroad. Nonetheless, there have been encouraging developments. For example, the German Federal Court of Justice issued an arrest warrant for an as-of-yet unnamed Islamic State commander.

What is unique about the threat to cultural heritage in Iraq, and what do you see as the biggest challenge to cultural heritage preservation there?

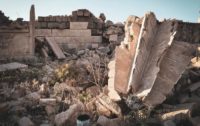

While certain patterns of conduct recur throughout history, especially systematic iconoclasm, I think that the complete breakdown of law and order and the rise of a militant group as powerful and coordinated as the Islamic State, in combination with the modern internet, made the situation in Iraq unique. An international audience primed to consume whatever new horror is uploaded to video-sharing sites and armed non-state actors ready to satisfy that demand in order to gain notoriety, funding, and recruits make an unholy combination. With the defeat of the Islamic State, the ‘hot conflict’ phase in Iraq has ended, but it is too early to know if this is truly the end. International disengagement could easily allow fighters that have gone underground to resurface and return Iraq to chaos.

Now more mundane and less visible threats are coming to the fore, including a serious lack of resources (personnel of heritage authorities in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq having received no salaries for months), uncontrolled urban/agricultural development, and lack of awareness. It is difficult to implement cohesive and systematic heritage preservation programs when a State is emaciated after nearly two decades of civil war and the population lacks even basic services.

Have you seen similar patterns of destruction elsewhere as you have seen in Iraq?

Bosnia and the wars of the Yugoslav succession come to mind immediately, though I would expect that most instances of ethnic cleansing follow a similar pattern as in Iraq. It is a standard strategy for perpetrators to attempt to ‘cleanse’ not only the human population, but also the architectural and natural landscape, especially religious buildings and landmarks. Have a look at Helen Walasek’s Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (Ashgate 2015), if you want to go into more detail.

This means it is important to understand cultural heritage destruction not just in terms of isolated crimes by crazed lunatics, but as a cold and calculated execution of a larger strategy targeting minorities and other vulnerable groups. Turning again to the Yazidi case, the destruction of Yazidi heritage was so much more than a war crime. It represented a systematic pattern of persecution (a crime against humanity) and evidence of the special intent to commit genocide.

Seán Fobbe is Chief Legal Officer of RASHID International, a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts, and other professionals dedicated to safeguarding the cultural heritage of Iraq. He leads a team of elite lawyers in their fight to secure the international rule of law, end the destruction of Iraqi heritage, and establish accountability for international crimes. RASHID International is a registered and audited non-profit organization headquartered in Germany.

Seán graduated from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität with a degree in law, earning an award for exceptionally outstanding achievements in international law and a coveted general distinction. He specializes in international law, with a focus on international humanitarian law, human rights law, and cultural heritage law.

Headshot courtesy of www.economy-business.de